What is it about books that make them the sine qua non of publishing? I think it's very simple. Great books have changed lives, have changed history. While there have been innumerable articles of great importance in magazines and newspapers, let's face it - they don't have the force of the classics of literature and non-fiction. Just about any reader can point to a book that has changed his or her life. Most of us can point to many different books that have had an equally strong impact.

We encounter these books at different ages. I know that many of the books I read when I was only 10- or 12-years-old made a huge impact then and still influence me today. The whole context of reading as a child was a unique emotional experience. As I grew older, I found books that suited my age, and continued to grow and mature with the extraordinary literature at my disposal.

Further, since Andrew Carnegie's philanthropic efforts, there has always been a great infrastructure for enjoying books. Most cities in North America have many fine libraries and bookstores. Books are everywhere! Supporting them also was a robust film industry that interpreted books in unexpected ways; as often as not driving us back to the original written version.

I fully entered the world of books in the early 1970s via book publishing, first as a bookseller, then as a traveling book sales rep, and then as a publisher. I still have very strong feelings about book publishing: most of the people I know who work in the book publishing industry feel as strongly. It's hard to get publishing out of your blood.

Book publishing is not the first form of publishing by any means - think cave drawings, scrolls and those dedicated monks with their beautiful manuscripts. But somehow book publishing has come to embody the idea of publishing more than any other form - when I say "publishing" you probably think books (perhaps even if you happen to be a newspaper publisher).

Yes, for most of us, books hold a unique emotional place in our hearts and minds. When it comes to imagine the so-called "death of print," we react in unison: Perhaps some kinds of print, but not books!

So then how to interpret the changes in the book publishing industry? We've still got Harry Potter, don't we? (With the last volume the greatest success of the series.)

What about all of the books for children, those marvelous classics. Surely they won't disappear? The bestsellers we read in hardcover and paperback; the fine non-fiction biographies and histories. These can't disappear, can they?

The Traditional Context of Book Publishing

Nearly all of us who are close to printing and publishing romanticize Gutenberg's invention of movable type (circa 1450) and cheerfully ignore the context that surrounded it. We cheerfully ignore the fact that printing was invented in China long before Gutenberg got near his printing press, and that in Korea a system of printing from movable metal type was developed around 1041.

We ignore that Gutenberg was a businessman as much as he was an "artist" - and possibly much more interested in business than art. (Unfortunately he was not a stellar businessman - by 1455 Gutenberg was effectively bankrupt.)

Not surprisingly, the history of publishing is well-documented in books. One such, a fine work, The Nature of the Book by Adrian Johns (The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1998), illustrates in 753 pages the very commercial nature of the book trade from its earliest days. Book publishing today is very much a descendant of those early efforts. It remains inescapably a commercial enterprise.

Certainly some not-for-profit groups, associations and government-subsidized efforts reduce the commercial pressure on their publication efforts as money-making ventures. But the vast majority of book publishers worldwide undertake their tasks with at least one eye on the bottom line, and this necessarily has a great impact on how the business of book publishing is conducted.

As someone who operated three different trade publishing companies in the 1970s, 80s and 90s, I began to see the modern challenge of book publishing as two-fold. The first was to get anyone to notice that a new book had even been published - as we've seen, hundreds of thousands of books are published each year, and it is expensive to get noticed with that much competition. Also (and particularly in the pre-Internet era), the sale of trade books relied on the distribution of those books to bookstores across America, or across Canada, or across...you name the country, and the cost of this broad geographic distribution was prohibitive except for the most high-profile titles. (Which tended to push publishers toward paying large advances for the few titles that were hoped to carry the many.)

I'll examine shortly the statistics that bear on these challenges. Some of them have changed in the last decades; many still apply.

Much more interesting to consider is the impact of the Internet on the creation, marketing, distribution and sale of books. The Internet is having an enormous impact on the future of book publishing - both in positive and negative ways. I'll examine this trend also.

At the same time there are other forces at work: eBooks, print-on-demand, the digital scanning of vast libraries and the conversion of certain books into other electronic formats. Each of these is playing a part in securing a fascinating future for my beloved The Wind in the Willows. Technology need not be destructive for book publishers; it can be a very positive force for change.

Types of Book Publishing

There are many kinds of book publishing. Most listings differ, but here is a representative sample of publishing types.

1. Trade publishing

(i) Hardcover

(ii) Trade paperback

(iii) Mass-market paperback

(iv) Children's books

(v) Religious books

2. Textbook publishing

(i) Textbooks in hardcover or paperback

(a) K-12 textbooks

(b) Secondary school textbooks

(c) Higher education: college and university textbooks

(d) Post formal institutional education (adult learning) textbooks

(ii) Ancillary texts, such as teacher or student guides

3. Reference publishing

(i) Encyclopedias

(ii) Directories

(iii) And numerous others

4. Reports, studies, etc. by not-for-profit publishers, government agencies, etc.

I'll stick with this short list of the types of book publishing for the time being, having it serve principally as a reminder that no discussion of book publishing can be authoritative without recognizing its varied species.

Hoovers, referenced below, reports that trade books account for 30 percent of the market, textbooks 25 percent, and professional books 15 percent. Those figures seem reasonable.

The Book Industry Study Group offers the following breakdown of small publishers:

The Scope of the Book Publishing Business in North America

According to Hoovers "The US book publishing industry consists of about 2,600 companies with combined annual revenue of $30 billion. Large US publishers include McGraw-Hill, Pearson PLC, John Wiley & Sons, and Scholastic. Some of the biggest publishers are units of large media companies, including HarperCollins (NewsCorp), Random House (Bertelsmann AG of Germany), and Simon & Schuster (CBS Corp). The industry is highly concentrated; the top 50 companies hold 80 percent of the market." This book industry report points to two different aspects of the industry: first, that there is a high degree of concentration at the top of the pyramid, and two, that most book publishing analysts grossly underestimate the size of the industry in the U.S. As pointed out above the Book Industry Study Group claims that in 2006 there were in fact 88,528 "active" publishers in the U.S., and nearly 68,000 had sales under $50,000 per year.

The same group estimates 2006 U.S. book sales at $35.7 billion, up 3.2 percent over 2005's total.

R.R. Bowker projects that U.S. title output in 2006 increased by more than 3% to 291,920 new titles and editions, up from the 282,500 published in 2005.

The Canadian Government's Statistics Canada agency counted 1,324 publishing companies in 2005, representing total sales of (CDN) $2.4 billion. It cautioned however that "the number of establishments is comprised mainly of small companies. Of the 1324 establishments for the industry only 444 were in the survey portion. This means that most of the movement in number of establishments from year to year comes from 884 companies that had under $50,000 in revenue."

Based on the U.S. figure of over 62,000 active publishers, one wonders if the Canadian figure should not be closer to 6,000 than 1,000, judging by the standard 10 to 1 ratio that holds for most industrial comparisons between the two countries. Canadian Books in Print listed 4,300 book publishers in the year 2000.

A unique aspect of the Canadian book publishing market is that 19 foreign-controlled publishers, which represented less than 6% of all companies surveyed, accounted for 59% of domestic book sales in 2004 (the percentage has increased). The Canadian book publishing industry is foreign-dominated.

Hoovers also remind us that "demand for books...is largely resistant to economic cycles." As I discuss in my blog entry "Economics and the Future of Publishing," this recession is thus far proving different, and the eventual outcome for book publishers remains to be seen.

The Practice of Book Publishing

Several unique practices have definitively characterized book publishing in the modern era:

1. Individual editors and/or publishers make individual decisions about what will or won't be published by their firm (at larger companies, a larger group may be involved in the decision).

This, as much as anything I believe is the cause of the transformation and decline of book publishing in the modern era. Who are these editors and publishers who have so much power to make life-and-death decisions on what books will or won't be published each year? They may have some kind of education associated with the history and/or practice of writing and literature. This ostensibly makes them "expert" in what constitutes "quality" in writing. But of course they are as susceptible as the rest of us to individual matters of taste, to bias and to lapses in judgment. Still their role within their respective companies is god-like - they make judgments of life or death, except in this case upon what will be published, rather than who will be sent to hell.

Furthermore, at the largest book publishers the decision is no longer generally about quality but more often about salability. Is that taught at Swarthmore?

Publishing courses are now abundant. Who really believes that you can take English majors in their twenties and "teach" them how to intuit what will be this year's bestseller? Twaddle.

2. At the same time, I consider it inarguable that most writers need good editors. William Zinsser, author of the classic text On Writing Well, wrote "The essence of writing is rewriting."

Ernest Hemingway is reputed to have told George Plimpton during an interview that he rewrote the ending to A Farewell to Arms 39 times before he was satisfied.

"Why so many rewrites?" Plimpton asked.

"Because," Hemingway responded, "I wanted to get the words right."

So while I argue above that editors can offer blocks to the publication of worthwhile books, in their key role, that of helping authors improve their texts, they are invaluable. That has been my consistent experience. The tales of great editors are legion, such as Maxwell Perkins and his role in shaping F. Scott Fitzgerald's prose. But a merely good editor can work magic also.

While many very poorly-written and poorly-edited books have become bestsellers, this doesn't obviate the general rule: a book written (and/or edited) with clarity in mind will succeed beyond a similar text that lacks such clarity.

3. The book industry has traditionally been a retail-based industry. Books are mostly bought in bookstores. The explosive growth of the major chain booksellers in the 1970s and onwards was continually lamented as representing some sort of "death of publishing." That dire prediction on the future of book publishing proved untrue. The major complaint was that the book chains would force publishers to take a pass on publishing important books in favor of "mindless" bestsellers. But with 350,000 books published in English last year that prediction has also proved false. Furthermore the numerous book superstores ordinarily feature a far broader inventory that the average independent bookseller.

Online bookselling by Amazon.com and its competitors has had an enormous impact on bookselling. Now anyone can quite easily obtain any of the 300,000+ new books that can't be found in the retail channel. The result is that never have so many different books been so easily, readily and inexpensively available.

Print-on-Demand Changes the Equation

This section links very clearly into the next. The premise is one that I often observe: a technology develops or evolves and a new industry (or sub-industry) is born. The improvement in print-on-demand (using a generic name for this type of print manufacturing) over the last decade has been astounding. As discussed elsewhere, most book publishers grew up in an industry where the consideration was between printing 3,000 copies or 5,000, hoping to shave perhaps 10-15% off the manufactured cost. What happens when you can print one book for 120%/per unit of the price of 3,000 books? An industry changes. The book publishing industry has changed because this is the new reality.

Vanity Publishing Becomes Self-Publishing

Vanity publishing always had a bad name. The concept was that some sucker would pay some huckster to print several thousand copies of their "terrifically important" manuscript that somehow had been cruelly overlooked by 300 New York agents and publishers, and turn that into the bestseller it had always deserved to be. Of course there were a few success stories to fuel the flames, but in many cases naïve authors found themselves with a large invoice and 2,999 copies of their book in the bedroom cupboard.

The big difference is distribution. In the old days of vanity publishing, those publishers had few mechanisms for book distribution, and even fewer chances of having their vanity publications taken seriously by any of the mainstream reviewers.

In the age of the Internet, distribution issues are significantly muted, and the reading public has discovered that they don't necessarily care what The New York Times says about an inexpensive book covering a topic in which they're interested.

This has led to the blossoming of Lulu.com and its brethren (see References for more information on Lulu.com), and I for one, will not lament the end of New York's hegemony on deciding what should be purchased and read.

Book Readership

Probably the most important document revealing key aspects of the future of book publishing is a 60-page report published by in June 2004 by the National Endowment for the Arts. Called Reading at Risk, the report presents the results from a 2002 survey (conducted by the Census Bureau) of 17,000 people aged 18 or older, who attended artistic performances, visited museums, watched broadcasts of arts programs, or read literature. The results are compared to similar surveys carried out in 1982 and 1992. The first sentence of the preface to the report notes that "Reading at Risk is not a report that the National Endowment for the Arts is happy to issue."

The survey asked respondents if during the previous twelve months they had read any novels, short stories, plays, or poetry in their leisure time (not for work or school). As the report notes, included were "popular genres such as mysteries, as well as contemporary and classic literary fiction. No distinctions were drawn on the quality of literary works." Literary non-fiction was apparently not included.

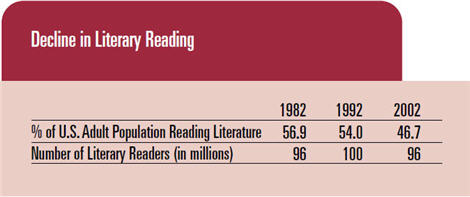

The results paint a grim picture for the future of the book. The charts (all taken directly from the report, and copyright of the National Endowment for the Arts) best reveal the tale:

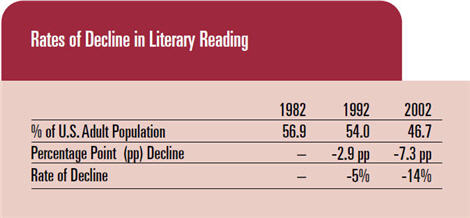

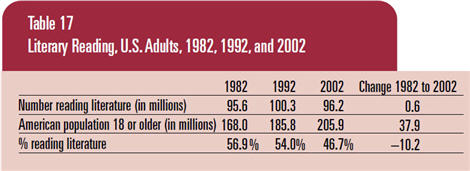

What is most notable in this first chart is an important anomaly between the number of literary readers and the percentage. Because of population increases, the total number of readers is constant over a 20-year period, while the percentage decline, as illustrated in the next figure is 7.3%, and by 2002, the rate of decline had increased to 14%!

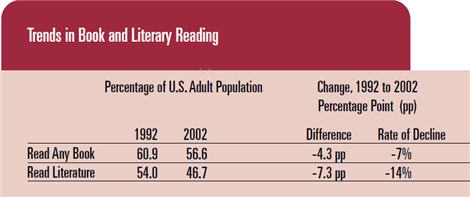

It's somewhat cold comfort that the rate of decline in the reading of "any book" decreased by half of the percentage of the decline in the reading of literature.

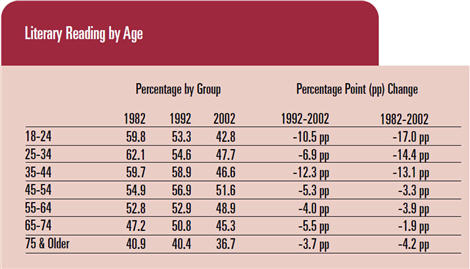

Not many will be surprised, though most of us will remain concerned, that the decline in reading is most pronounced in the young, although the following chart encompasses those up to the age of 44! Even the "elderly" are partaking of the slaughter, but in far more modest numbers.

Looking at similar results from a slightly different statistical perspective, while the U.S. population increased by nearly 40% between 1982 and 2002, the percentage reading literature dropped by just over 10%.

What conclusions to draw from this arguably grim data? I think that the pessimist's viewpoint is well-represented by these charts (and more so in the original report - recommended reading). But it is worth focusing on the brighter side of the picture. Two data points stand out: while there is a clear shift away from literary reading, the reading of the broad range of books published does not show as steep a decline. Also, the North American population will continue to increase, and this will to some extent ameliorate the trend from the publishers' perspective - although the nature of what they publish will have to change if they wish to hold their own against the trends so clearly illustrated here.

The other question remains as to what percentage of all books sold annually could be classified as "literary." I suspect the percentage is modest. (I'm still looking for a data source to illuminate this question.)

A few key data points:

What makes this report both more important and more unsettling than its predecessor is that it is of course more timely, but also that it moves beyond the single category of "literary reading," taking a broader view of publishing. And that broader view is a bleaker view.

- Nearly half of all Americans ages 18 to 24 read no books for pleasure.

- The percentage of 18- to 44-year-olds who read a book fell 7 points from 1992 to 2002.

- The percentage of 17-year-olds who read nothing at all for pleasure has doubled over a 20-year period.

- Although nominal spending on books grew from 1985 to 2005, average annual household spending on books dropped 14% when adjusted for inflation.

Future of Book Publishing -- Trends & Outlook

While the book publishing industry has begun to come to terms with some of the opportunities afforded by the Internet, I fear that this is thus far a case of too little, too late. Of course it's not merely missed opportunities on the Internet and the Web. More fundamentally, it appears that competing media are slowly eroding the economic base of publishing. Twenty years ago television and music were distracting for the young. In combination with chat, social networking sites, mobile phones and more, the book has certainly met its match.

Thursday, January 1, 2009

Thad McIlroy's Take On Book Publishing Trends And Outlook

This article is just right on the spot with regards to outlining book publishing its trends and what it is projected to be in the next few years.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

Thank you so much for reprinting my article. That what it's there for.

Just an FYI to your readers: my whole site (which covers the full spectrum of publishing) is available at:

www.thefutureofpublishing.com

Regards,

Thad

Post a Comment